Blog – alanza.xyz

ROBBIE LYMAN

A five-year project

In 2020 I was part of the inaugural group of participants in the Women in Groups, Geometry and Dynamics retreat. Since the ball got rolling before COVID hit, the retreat didn't physically happen for more than a year, and we did a lot of meeting on Zoom. Five years later, I think my research group is finally planning to send a draft around to potentially interested experts next week.

- In the beginning

- Five years on Zoom

- Never the same

- The project

- A CAT(-1) space

- Can I read it?

In the beginning

I remember hoping that the retreat would help me build community, find an "adult researcher" set of problems to work on, and be a nice way to transition from grad student to postdoc. WiGGD was a huge success at all of these things. It's a little funny to look back on the person who had those thoughts. I'm pretty okay (improving, anyway) on the whole about thinking intentionally about setting up future versions of me to have a good time. It's easy for me to teeter over into either the pitfall of "I cannot control the future, and so therefore it is bad for me to try to influence it at all" or "I have wildly specific desires about the future and I will do everything in my power to achieve them because it is what I deserve." I'm sure I was doing this at the time in other ways, but it is nice to see that instead, I appear to have recognized WiGGD as a good "next step" to take and taken it.

Five years on Zoom

Our group met to discuss our project approximately every week on Zoom for five years. Throughout all of that time we have been, the four of us, scattered to the four winds. Elizabeth Field and I graduated with our PhDs and moved to Utah and New York, respectively. Radhika Gupta must have been in Bristol and Emily in Utah when we started, but they moved to Temple and Wesleyan, respectively, and then Radhika to India. After our postdocs, Elizabeth and I started tenure-track jobs, which took Elizabeth even further west to Washington. This makes the sweet spot for our Zoom meetings extremely narrow: almost all of those five years we have met at 10AM Eastern, which is 7AM for Elizabeth and 7:30PM for Radhika. They're champions for even being willing to entertain the idea of meeting consistently at those times, much less following through week after week, year after year.

Meeting on Zoom can be so difficult—I find sometimes that it’s super easy for my attention to wander for several minutes—and then when I bring it back I’m lost for several more trying unobtrusively to find the thread of the conversation. But also it’s been a lovely group of friends to chat to every week.

Never the same

I already mentioned that none of us have the same academic job that we had at the beginning of the project, but we’ve also advanced in our lives significantly over that time. Both Emily and Radhika got married, Emily had a baby, Elizabeth got a dog and began fostering and has now adopted a teenager. I transitioned, recorded an album, and learned more seriously to code.

Returning to some of the earlier sections of the paper to reread, I had to laugh a couple times at arguments that I remember being crystal clear to me when we thought them up but made no sense to our wiser eyes. Many many many times over the course of the project we would spend significant chunks of our meeting rehearsing the big picture idea of our project to each other hoping to try to pick up the thread where a previous version of ourselves had put it down.

The project

I don’t think I’ll tell you too much about the math, at least not the stuff that actually made it into the paper, but here’s the jargon said in a weird way; I’m gonna use the words but also try to signpost what role they’re playing without actually defining anything: using an invariant called the conformal dimension of an object called the Bowditch boundary, we show that a certain family of things called Coxeter groups with a certain common property, namely “their defining graph being complete with all edge labels at least 3”, that gives them certain superficial similarities, namely “their visual boundary is something called a Menger curve when the defining graph has at least five vertices”, actually fall into infinitely many distinct categories called quasi-isometry types.

This result is novel in some ways—computing conformal dimension for the Bowditch boundary is unusual, as is using the common method “constructing Gromov’s round trees” for situations like ours, but it also isn’t unexpected; the topology of the visual boundary (i.e. its being a Menger curve) is known to be a rather weak property to have in common. In fact, our results fall short of what we expect to be true, namely that for our family of groups, having the same quasi-isometry type should happen only when the much stronger property of being isomorphic (i.e. being associated to the same defining graph, say) is true.

A CAT(-1) space

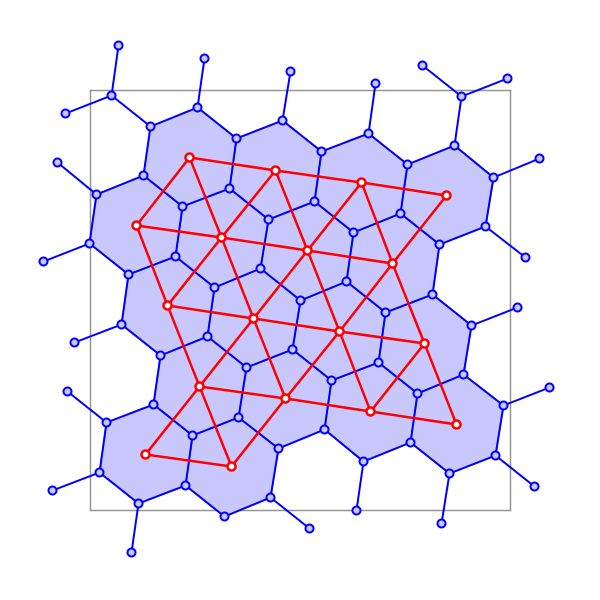

One really fun and very challenging part of this project has been constructing and understanding a geometry to associate to these groups. Let me explain: as you know from observing honeycombs, by laying regular hexagons down, you can tile the plane without overlaps or gaps.

(I found the above image on Peter Stampfli’s blog; so far as I can tell, he made it himself. Isn’t it pretty?)

Starting with such a tiling, if you draw the straight lines that cut through the middle of every edge of the hexagonal tiling, you obtain another tiling of the plane, this time by equilateral triangles. The angles of an equilateral triangle are, as you know, in radians all equal to $\frac{\pi}{3}$. If you put a mirror down on the hexagonal tiling along each of these lines that make up the triangular tiling, and you looked alternately through the mirror or around at your surroundings, you wouldn’t see a difference—the symmetry in the mirror preserves the tiling. The Coxeter group with defining graph the complete graph on three vertices (i.e. a triangle) with all edges labeled three, is the collection of all symmetries of the plane you get by repeatedly using these “triangle walls” as mirrors.

In general, keeping the number of vertices of the graph equal to three, but varying your edge labels, you start to want triangles that are impossible: if the edge label is $n$, you want a triangle where that corresponding angle is equal to $\frac{\pi}{n}$. But in Euclidean geometry, the angles have to add up to $\pi$, so you can’t produce a triangle where each angle is at most $\frac{\pi}{3}$ but some angle is smaller.

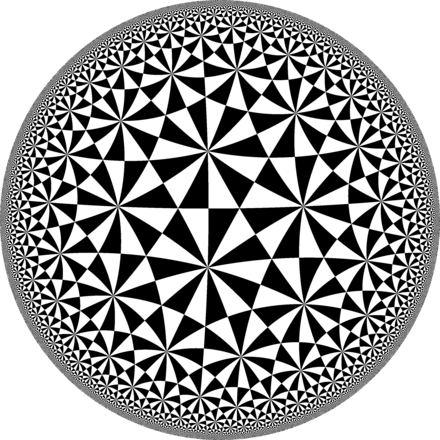

However, in hyperbolic geometry, the most beautiful (certainly my favorite, anyway) form of non-Euclidean geometry, this is possible! I’m sure those of you who think “this is all well and good, but what’s the use of this stuff, where is it in the real world” are already fully tabbing away, but let me suggest that hyperbolic geometry is the geometry of kale leaves and anything whose area grows, despite all odds, only about as fast as its perimeter. Trees (like, mathematical, computer sciencey trees) are a good model for hyperbolic geometry in a certain precise sense. Here’s a tiling of the hyperbolic plane by the so-called “(2,3,7) triangle group”: just to be clear, that’s a triangle where one angle is a right angle ($\frac{\pi}{2}$), one angle is $\frac{\pi}{3}$, and the last angle, which would have to be $\frac{\pi}{6}$ in a Euclidean triangle, is instead $\frac{\pi}{7}$.

(The above image was uploaded to the Wikimedia project by user Tamfang; it’s their own work!)

So much for letting the labels on the edges change. What would it mean to add more vertices? One super beautiful and possibly surprising fact is that all of these groups have a geometry modeled on a 3-dimensional version of the hyperbolic plane. The ideas that go into the proof of this fact are gorgeous, a 1970 theorem of E. M. Andreev that bore a truly beautiful fruit in Bill Thurston’s conjecture (and Grigori Perelman’s proof of) “geometrization” for 3-dimensional manifolds.

Interestingly, as you add more vertices on beyond four (oh the places you’ll go!) the dimension stops increasing. In some sense, I got the strong feeling that you wanted to take the three-dimensional hyperbolic picture, for which the basic building block is more or less a tetrahedron (triangular pyramid) with some wishy-washiness about what to do at the tips, and … overglue them somehow. Like, you still want a vertex or a tip of the pyramid shape for every group of three vertices in your defining graph, but as you add more vertices to the graph, the number of tips increases and the shape gets weird and spiky. Surprising me, we were able to prove that this actually works and produces a geometry satisfying a nice property. (The property is called CAT(-1). The letters are initials for Cartan, Alexandrov and Topogonov, three geometers Gromov credited with thinking relevant thoughts, and $-1$ could be any real number, although the most relevant choices are $-1$, $0$ and $1$. The choice $-1$ suggests “hyperbolic”, a $0$ would be “Euclidean”, and a $1$ would be “spherical”.)

Can I read it?

You’re so sweet for reading this blog post! Sure, I’d love to send you a draft if you want—shoot me an email. Otherwise it should go up on the arXiv in a couple weeks at the latest.